I have always found Descartes a problematic thinker. On the one hand I am drawn (as my previous post indicates) to his narrative of solitary philosophizing, as well as to the fine and clear arguments that are set out in his central works (the Discourse on Method and the Meditations), to how stimulating and suspiciously wrong they seem, and to the lucidity of his mechanical philosophy which conceives of the universe in terms of quantifiable matter and motion, surely the most useful and plausible way of understanding it. Yet, on the other hand, I cannot escape the feeling that Descartes represents a crucial point from which much of what is most dispiriting and downright wrong about the modern world stems. My reservations focus both on his purported philosophical method, and on the philosophy that resulted from it.

Descartes explicitly rejected the study of letters, and famously likened his philosophical approach to pulling down a building and rebuilding from the foundations up. Whatever the influences on his philosophy (and they are certainly there, from both ancient and medieval philosophy), his rhetorical strategy was to dismiss history and tradition as valueless and to emphasize the novelty and originality of his ideas. It is an undoubtedly seductive approach, and it is not hard to imagine its appeal: why be burdened with the laborious task of ploughing through complex, heavy philosophical tomes, when one can follow Descartes’ brilliantly simple and clear method and reasoning with a more certain guarantee of arriving at philosophical truth?

This approach has been hugely influential on modernity, to the extent that a cult of novelty and originality has followed in its wake. Of course, Descartes can hardly be held entirely responsible for this; nevertheless, as arguably the key figure in the emergence of ‘modern philosophy’, he can be regarded as one of the key contributors to this overvaluing of the new and the original. One of the consequences of this development is the undervaluing of history and the wisdom of the past. We relentlessly quest after new ideas and ways of thinking, and we contract our scope to the present and only very recent past.

Moreover, Descartes’ rarefied philosophical approach, one that consciously steered away from the world and towards the abstraction of reasoning of the mind, compounds the problems of a focus on novelty and originality. Descartes’ approach separates ideas from their social and historical reality, underscoring the philosophical concern (a highly fraught concern, in my view) with supposedly timeless truths.

In the sphere of economics, for example, current conventional thinking insists that markets are never wrong, that economies fail when a market is not fully free, that austerity is the correct response to budget deficits, and that a ‘shock doctrine’ needs to be applied to failing economies. Yet all of this is dogma based in large part on abstract reasoning rather than actual social and historical experience. It represents comparatively new ideas, supposedly at the cutting edge of economic thought, and it dismisses the value of studying alternative theories and the concrete reality of the past.

And there is another way in which the example of contemporary economic thought might be compared analogously with Descartes’ philosophy. One of the most striking aspects of the currently dominant economic theory is its presentation as a science: economics can be understood, according to this view, as a set of iron laws. What follows from this is an approach to economics in which the human, the irrational and the moral are absent. Focus is exclusively directed towards what is quantifiable and measurable. Hence, austerity and shock doctrines arise from a mentality in which the quantifiable is all that matters—the human suffering that results from these policies is of no concern, since suffering cannot be measured in the way that GDP can.

Descartes’ mechanical philosophy (one that also owed much to many other thinkers of the period, notably Galileo and Hobbes) involved a radical shift from viewing the universe in terms of qualities to understanding it as something essentially measurable and quantifiable. It is the basis of modern science. The importance of this intellectual achievement is beyond question; as I suggest above, the mechanistic view is both more plausible and more useful than what came before.

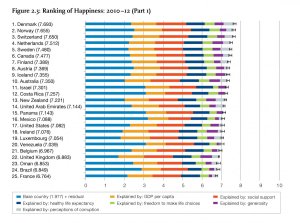

Happiness, once thought of as a subjective quality, is increasingly now subject to attempted objective quantification

But it is worth reflecting on what was lost in this philosophical revolution, and also on what some of its (largely unintended) consequences have been. Gone was a universe that might be understood in terms of spirits, of qualitatively different parts; the universe had been rationalized as working according to a set of unchanging and rigid scientific laws, as something that could be worked out by measuring and understanding the laws. It was perhaps inevitable that this approach, at first restricted in its application largely to an understanding of the natural world and the workings of the universe, would eventually be extended to almost everything: health, education, social conditions, the workplace, the economy are now routinely reduced to metrics and the quantifiable, with little regard paid to unquantifiable qualities (although even in respect of these attempts are made to ‘measure’ satisfaction, happiness, quality of life, and so on).

Descartes did not himself view the universe solely in material terms. Famously he set out arguments that, he believed, proved the existence of God; and he held to a dualist philosophy in which, just as the universe consisted of both matter subject to scientific laws and God, so humans were made up of a material body and an immaterial mind. But, however much they endeavoured to avoid a view on the universe as akin to a coldly rational machine, neither his proofs of God’s existence nor his dualism have ever been convincing. Indeed, my own suspicion is that his arguments for God’s existence and the immortality of the soul were decidedly secondary to his main concern of outlining a mechanistic philosophy. It was perhaps the implications of that mechanistic philosophy that compelled him to find ways of demonstrating that God and the spiritual nevertheless still have a place somewhere inside the universe: maybe he sensed the potentially bleak universe that may arise once all that is not quantifiable has been leeched out of it.

To blame Descartes for the modern obsession with metrics and the quantifiable, for the move away from the qualitative and the moral, and with the cult of novelty and originality would, of course, be unfair. Descartes could not foresee such things as the dominance of the scientific worldview. Even so, if we want to locate one of the roots of the modern political, economic, social and cultural malaise, then I suggest that the mechanical philosophy of Descartes is a good place to look.